In a previous installment, I asked the obvious questions about the intangible, heinous, and inexorable social power of the Islamic State:

Is this power derived from religious faith? If so, is it only Islam we should fear, or is this just one more iteration of the violence endemic to all classic monotheism?

I ventured the suggestion that George Packer has, the last week, brought us close to the beginning of an answer: the Islamic State’s indiscriminate massacre and torture are acts of purification, and the Jordanian pilot’s slow death by fire the ultimate sacrifice. The blood and dread serves to excite, unite, and grow the new community.

But before traveling further down this explanatory path, I want to back up for some context setting and take a look at what is, or at least should be, the larger debate.

There is no better place to start than new atheist and cognitive neuroscientist Sam Harris, who has more than anyone helped galvanize the post 9/11 American imagination. In his best-selling End of Faith (2004) Harris announces that Americans should fear “the fall of civilization” given the new close proximity of religious fanatics to weapons of mass destruction. Religion – more exactly, religious faith – “has been the explicit cause of literally millions of deaths in the last ten years” and the “most prolific source of violence in our history” (26-27). “The problem is with Islam itself.” The reason Osama bin Laden intended to kill innocent men, women, and children is obvious.” Bin Laden believes “in the literal truth of the Koran.”

Some of Harris’ arguments are quite persuasive. Consider this one:

Subtract the Muslim belief in martyrdom and jihad, and the actions of suicide bombers become completely unintelligible, as does the spectacle of the public jubilation that invariably follows their deaths; insert these peculiar beliefs, and one can only marvel that suicide bombing is not more widespread (33).

Harris also points to results from a 2002 global survey of over 38,000 Muslims. The survey revealed a shocking acceptance of suicide bombing and violence against civilian targets: 82% of Muslims in Lebanon endorsed suicide bombing and violence against civilian targets, 73% in Ivory Coast, 66% in Nigeria, 65% in Jordan. A number of countries not included in the survey would have shown percentages higher than Lebanon’s 82%.

Holy War. An innocent, secular America caught in the cross hairs of the latest man of fanatical irrational faith, speaking on behalf of the Almighty. Or maybe not. In her newly released Fields of Blood, Karen Armstrong tracks the interplay of religion and violence from the dawn of civilization up to today’s global jihad. For much of our history, Armstrong argues, all violence was sacred. We devised rituals to cope with our need to destroy beautiful and awe-inspiring animals when we roamed the wilderness freely in the dangerous hunt for food. Just so, the ruling elite of the new agrarian civilizations devised stories about their special mingling with gods – in need of some way to make intelligible the inescapable ‘structural violence’ in their communities, specifically, their control and exploitation of most the human population (land-working peasants). If the economics of civilization has always been intrinsically violent and religion intrinsically political, then religion has always been ‘implicated’ in violence, but never its ‘sole cause.’ If we really want to understand the causes of the insidious violence in the Middle East, we cannot continue to make a scape goat out of religion.

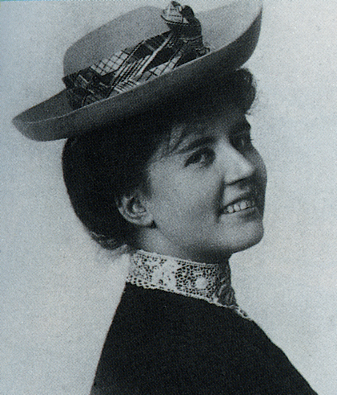

When Salon recently asked Armstrong about Sam Harris’s (and Bill Maher’s) opinion that there is “something inherently violent about Islam,” Armstrong responded this way:

It fills me with despair, because this is the sort of talk that led to the concentration camps in Europe. This is the kind of thing people were saying about Jews in the 1930s and ’40s in Europe. . . . Germany was one of the most cultivated countries in Europe; it was one of the leading players in the Enlightenment, and yet we discovered that a concentration camp can exist within the same vicinity as a university. . . . [John Locke] said that a master had absolute and despotical power over a slave, which included the right to kill him at any time. That was the attitude that we British and French colonists took to the colonies, that these people didn’t have the same rights as us. I hear that same disdain in Sam Harris, and it fills me with a sense of dread and despair.

To the new atheist complaint over the ‘irrationality’ of religion, Armstrong reminds us that we will always have ‘myth,’ since that is what we are.

I am inclined to think that both of these polarizing stances carries an important truth. But I am more certain about an ironic similarity between Harris and Armstrong, one that has so far gone unnoticed. It is where they agree, perhaps inadvertently, that they are each deeply flawed.

More to come soon.