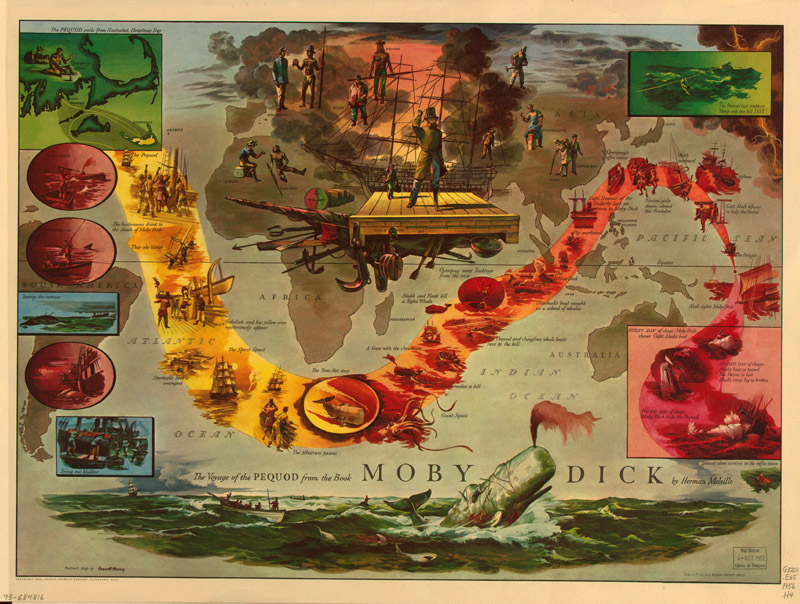

Speaking of animals and the law, I know of no where else to first turn but Melville:

Most mariners cherish a very superstitious feeling about seals, arising not only from their peculiar tones when in distress, but also from the human look of their round heads and semi-intelligent faces, seen peeringly uprising from the water alongside. In the sea, under certain circumstances, seals have more than once been mistaken for men (The Whale, 570).

And vice versa. A San Diego fellow just last year met his watery grave by fooling a poor Great White (flapping as he did a ways out in a black wet suit). When one thinks he is biting into a nice macaroni noodle, behold! a plastic coated worm!

But as with seals, so with pigs. The posh Christopher Hitchens attempts an almost identical theory for the timeless trepidation over the pig:

The simultaneous attraction and repulsion derived from an anthropological root: the look of the pig, and the taste of the pig, and the dying yells of the pig, and the evident intelligence of the pig, were too uncomfortably reminiscent of the human (god is not Great, 40).

But here now is the thesis: Is not there a dispositional reason for our denigration of the pig? Is not there just something swinish, something messy, muddy, and chaotic, in their very nature? They cannot help but do otherwise, right? As with humans, so with pigs; their freedom of character lies mainly in their inherited situation:

Orwell actually did dislike pigs, as a consequence of his failure as a small farmer, and this revulsion is shared by many adults who have had to work with these difficult animals in the agricultural conditions. Crammed together in sties, pigs tend to act swinishly, as it were, and to have noisy and nasty fights. It was not unknown for them to eat their own young and even their own excrement, while their tendency to random and loose gallantry is often painful to the more fastidious eye. But it has often been noticed that pigs left to their own devices, and granted sufficient space, will keep themselves very clean, arrange little bowers, bring up families, and engage in social interaction with other pigs. The creatures also display many signs of intelligence, and it has been calculated that the crucial ratio – between brain weight and body weight – is almost as high with them as it is in dolphins. There is great adaptability between the pig and its environment, as witness wild boars and “feral pigs” as opposed to the placid porkers and frisky piglets of our more immediate experience.

Hitchens, for some narrative reason only known to my unconscious intuition, provides this information on pigs before getting on to the business of god without any trace of explicit theorizing on Situationism. Yet it is this peculiar note on pigs that betrays Hitchens’ adoption of the general thesis. And as with pigs, so with cattle. Clarence Darrow made exactly this argument regarding cattle, as provided by the recent entry of the Situationist:

Some of you people have lived in the country. It’s prettier than it is here. And if you have ever lived on a farm you understand that if you put a lot of cattle in a field, when the pasture is short they will jump over the fence; but put them in a good field where there is plenty of pasture, and they will be law-abiding cattle to the end of time.

Not content with metaphor and analogy, Darrow went on to draw a scientific correspondence between human mammals, cattle, and in fact the rest of the animal kingdom. Darrow addressed the prisoners in the Chicago jail:

The human animal is just like the rest of the animals, only a little more so. The same thing that governs in the one governs in the other. . . . nine-tenths of you are in jail because you did not have a good lawyer and of course you did not have a good lawyer because you did not have enough money to pay a good lawyer. There is no very great danger of a rich man going to jail. . . . I will guarantee to take from this jail, or any jail in the world, five hundred men who have been the worst criminals and law breakers who ever got into jail, and I will go down to our lowest streets and take five hundred of the most hardened prostitutes, and go out somewhere where there is plenty of land, and will give them a chance to make a living, and they will be as good people as the average in the community. There is a remedy for the sort of condition we see here. The world never finds it out, or when it does find it out it does not enforce it. You may pass a law punishing every person with death for burglary, and it will make no difference. Men will commit it just the same. In England there was a time when one hundred different offenses were punishable with death, and it made no difference. The English people strangely found out that so fast as they repealed the severe penalties and so fast as they did away with punishing men by death, crime decreased instead of increased; that the smaller the penalty the fewer the crimes. Hanging men in our county jails does not prevent murder. It makes murderers. And this has been the history of the world. It’s easy to see how to do away with what we call crime. It is not so easy to do it. I will tell you how to do it. It can be done by giving the people a chance to live — by destroying special privileges. So long as big criminals can get the coal fields, so long as the big criminals have control of the city council and get the public streets for street cars and gas rights, this is bound to send thousands of poor people to jail. So long as men are allowed to monopolize all the earth, and compel others to live on such terms as these men see fit to make, then you are bound to get into jail. The only way in the world to abolish crime and criminals is to abolish the big ones and the little ones together. Make fair conditions of life. Give men a chance to live. Abolish the right of private ownership of land, abolish monopoly, make the world partners in production, partners in the good things of life. Nobody would steal if he could get something of his own some easier way. Nobody will commit burglary when he has a house full. No girl will go out on the streets when she has a comfortable place at home. The man who owns a sweatshop or a department store may not be to blame himself for the condition of his girls, but when he pays them five dollars, three dollars, and two dollars a week, I wonder where he thinks they will get the rest of their money to live. The only way to cure these conditions is by equality. There should be no jails. They do not accomplish what they pretend to accomplish. If you would wipe them out, there would be no more criminals than now. They terrorize nobody. They are a blot upon civilization, and a jail is an evidence of the lack of charity of the people on the outside who make the jails and fill them with the victims of their greed.

You can read the entire address at the Situationist here.

Lest the reader think they have the full truth of what transpired during this address, consider H.L. recounting of Darrow’s speech at the Scopes Monkey Trial:

You have but a dim notion of it who have only read. It was not designed for reading, but for hearing. The clanging of it was as important as the logic. It rose like a wind and ended like a flourish of bugles. The very judge on the bench, toward the end of it, began to look uneasy (The Baltimore Evening Sun, July 14, 1925).

But comparing man – the crowning jewel of creation, created from the dust of the earth to take dominion over everything living and non-living thing; comparing this lord of creation to the mere beast of the field; this will no doubt be ludicrous and shameful to many contemporary Americans, and with certainty, to an even larger percentage of our beloved yokels. And so it remains true that, at times, the looking at nature objectively, and the intellectual progress sure to follow in its wake, will not be permitted in our great country. The same was true for Darrow’s own close environment. Yet, this was no cause for locking truth away in the libraries of the elite. Darrow spoke of man qua animal boldly. In fact, Darrow had to deal with this very issue formally while confronting William Jennings Bryan, a circumstance that very well could have contributed to Bryan’s close trailing death. Menken, an eye-witness, recounted the scene:

Once he had one leg in the White House and the nation trembled under his roars. Now he is a tinpot pope in the Coca-Cola belt and a brother to the forlorn pastors who belabor half-wits in galvanized iron tabernacles behind the railroad yards. His own speech was a grotesque performance and downright touching in its imbecility. Its climax came when he launched into a furious denunciation of the doctrine that man is a mammal. It seemed a sheer impossibility that an illiterate man should stand up in public and discharge any such nonsense. Yet the poor old fellow did it. Darrow stared incredulous. Malone sat with his mouth wide open. Hays indulged himself in one of his sardonic chuckles. Stewart and Bryan fils looked extremely uneasy, but the old mountebank ranted on. To call a man a mammal, it appeared, was to flout the revelation of God. The certain effect of the doctrine would be to destroy morality and promote infidelity. The defense let it pass. The lily needed no gilding. (July 17).

And so as it is, American law, reverently obeying demotic Custom, has been wed to American Religion. If man be an eternal soul with disposition to either do good or to do evil, bound for either eternal bliss and reward or everlasting torture and condemnation, either right now fully of the world or a God-filled saint of the universal ecclesia, then it follows plainly that man cannot be a social animal. And if not a social animal, bound by the same laws as pigs and cattle, then society can continue resting content with a convenient and comfortable two-tiered universe: Us and the Other; the Good and the Bad.

As a social animal, however, Darrow’s opinion of ‘justice’ might well be described by an alternative dualism; as Melville had it, man is as the great Sperm Whale, once yanked from its natural social environment and enslaved: to be, in the eyes of the law, either a Fast-Fish or a Loose-Fish (434-35):

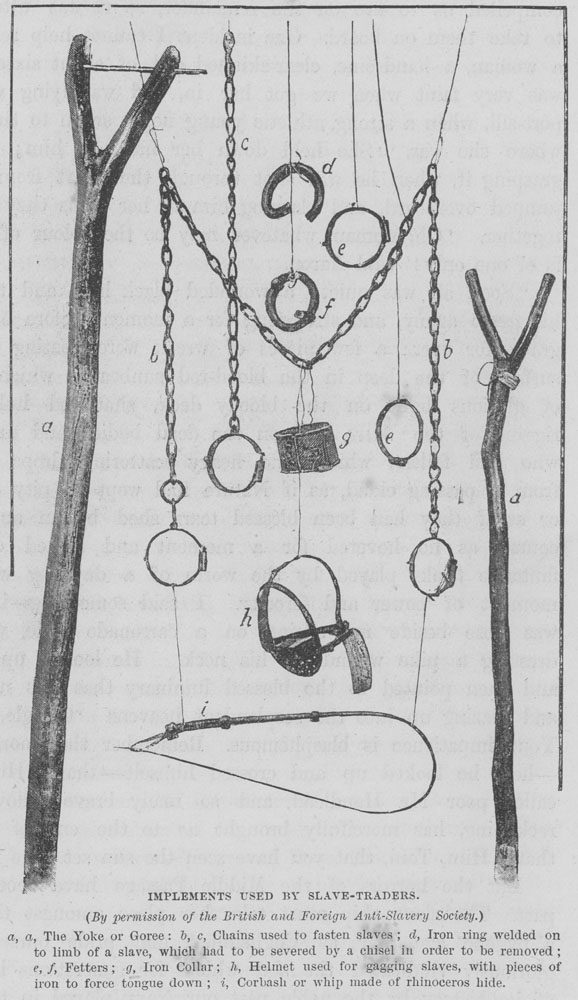

Is it not a saying in every one’s mouth, Possession is half of the law: that is, regardless of how the thing came into possession? But often possession is the whole of the law. What are the sinews and souls of Russian serfs and Republican slaves but Fast-Fish, whereof possession is the whole of the law? What to the rapacious landlord is the widow’s last mite but a Fast-Fish? . . . What is the ruinous discount which Mordecai, the broker, gets from poor Woebegone, the bankrupt, on a loan to keep Woebegone’s family from starvation; what is that ruinous discount but a Fast-Fish? What is the Archbishop of Savesoul’s income of 100,000 seized from the scant bread and cheese of hundreds of thousands of broken-backed laborers . . . but a Fast-Fish? . . . What was American in 1492 but a Loose-Fish? What all men’s minds and opinions but Loose-Fish? What is the principle of religious belief in them but a Loose-Fish? What to the ostentatious smuggling verbalists are the thoughts of thinkers but Loose-Fish? What is the great globe itself but a Loose-Fish? And what are you, reader, but a Loose-Fish and Fast-Fish, too?